Sustainability in the poultry production chain is often regarded as a key objective. Of course, the interpretation and definition of sustainability can be different from company to company. Some companies might focus on reducing the use of imported cereals or oil grains, while others might focus on improving feed efficiency or consumer safety, and some may try to improve egg quality to reduce waste. So, the balance among the elements of the sustainability triangle – people, planet and profit – can vary.

Waste in the poultry production chain

One of the main costs having an impact on sustainability in an integrated poultry company is product waste. This can be due to: rejections of whole carcasses or parts of the carcasses in processing plants, poor uniformity of broiler flocks resulting in lower carcass yields because of difficulties in optimizing the settings, increased transportation mortality, increased growing mortality or day-old chick mortality, non-hatching eggs due to shell quality or dirtiness, low hatchability because of low fertility or poor egg quality or errors during incubation.

One of the main waste factors in the poultry meat production chain occurs in the hatchery, the ‘crossroad’ in an integration. Incubation is a continuous process so the susceptibility to bacterial contamination in the hatchery is high, and stringent incoming procedures need to be in place in order to improve egg quality and safeguard day-old chick production.

The incoming eggs need to be of excellent quality, both internally and externally, and free from bacterial or fungal contaminations. It has been established that eggs are not sterile and that bacteria are present in both yolk and albumen, but that the diversity is higher in the yolk than in the albumen.

Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes are the main phyla present in yolk and albumen. During incubation, the microbial diversity increases slightly in the yolk while it decreases in the egg white. According to Jin et al. (2022), this is likely due to the antibacterial activities of the albumen (e.g. lysozyme). Still, plenty of harmful bacteria can be present in the egg, resulting in increased embryonic mortality, often accompanied by an increased frequency of eggs exploding during incubation (= egg bangers). This is the result of bacteria generating gas (e.g., Pseudomonas, but also Salmonella or E. coli). Therefore, improving the barrier against bacterial or fungal penetration into the egg is essential to avoiding waste in the poultry production process.

Improve egg quality

Protein is important in the production process of eggs, because it determines the matrix of the shell and it has antibacterial properties. Improving the egg’s protein quality is essential to improving sustainable egg production – as work done by Wistedt et al. (2019), Vlockova et al. (2018), and Negoita et al. (2017) has shown. Their research has found that shell weight continues to grow until the hens reach 50 weeks of age, after which it reaches a plateau. Until that age, shell thickness does not decline significantly; after that age, shell thickness declines because the eggs grow larger.

That research has also demonstrated that shell breaking strength declines as the hen ages, despite the fact that the calcium blood levels increase– which indicates that calcium is not the limiting factor in shell breaking strength and shell quality but that the organic part is more important.

By focusing on the organic part, we can benefit on several levels: not only in terms of improved self-defense mechanisms against bacterial and fungal penetration into the egg – hence, reducing the incidence of egg bangers and improving day-old chick quality – but also in terms of better egg quality, which results in fewer non-hatching eggs or second-grade eggs.

Minimizing egg bangers

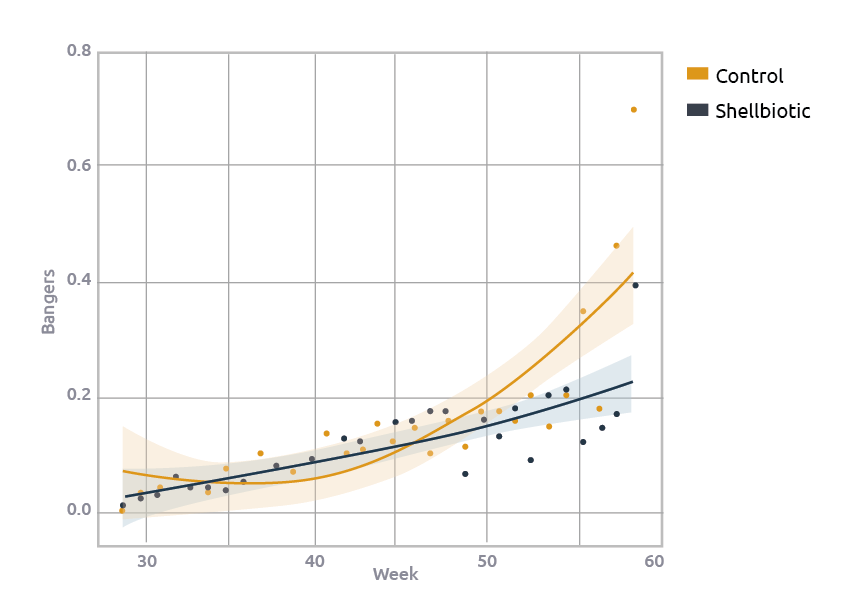

Agrimprove experts have developed a product called ‘Shellbiotic’ that focuses on performance, egg quality, and day-old chick quality. In a bigger field trial within a Scandinavian integration, it was proven that Shellbiotic was able to significantly reduce the number of eggs exploding during incubation. Although no bacterial profile was established, these data strongly suggest that the internal egg was less contaminated with gas-forming bacteria.

At the end of the trial, the control group showed almost twice the number of eggs exploding compared to the Shellbiotic group (Figure 1). This not only has an impact on hatchability but also on the bacterial contamination of the day-old chicks, which can eventually result in yolk sac infections. Moreover, although egg bangers can be relatively low in absolute numbers or percentages, they can contaminate an entire setter or hatcher during incubation.

So, measurements should be taken to minimize egg bangers and improve egg quality. Good egg hygiene procedures are key in this, as egg bangers are often related to the hygiene status of the hatching eggs, the health status of the breeders, and the hygiene status of the farm. In combination with shell quality and egg quality in general, these are the parameters that mainly determine the risk of bacterial and fungal penetration into the egg.

The risk of egg bangers can be reduced by improving all of the above-mentioned factors. The cuticula and the protein matrix in the shell and shell membranes are extremely important in the defense mechanism of the egg, as they prevent bacterial or fungal penetration to the egg’s core. Not only do they possess antibacterial molecules like lysozyme, they also form a physical barrier to pathogens. So, egg production and day-old chick production not only benefit from a good calcium metabolism but even more from an optimum protein metabolism.

Using Shellbiotic to improve egg quality and bone strength

Earlier work on commercial layers has shown that using Shellbiotic in the layer feed contributes to better shell breaking strength (Table 1) as well as to better bone breaking strength (Table 2). As is generally known, breeding companies try to minimize the growth of the egg’s weight after peak production to avoid oversized eggs as much as possible. This means that shell weight and albumen weight in commercial layers no longer increase significantly after the oviduct has fully matured, although egg size continues to grow slightly because of the increase in yolk weight. This can result in a minimum decrease of shell thickness, which might also affect shell breaking strength. Nevertheless, the decline in shell membrane thickness – which occurs as the hen or breeder ages – has a greater effect on shell breaking strength.

Both the shell and the bone have organic (proteins/collagen) and inorganic (Ca/P) components – and both determine breaking strength as well as porosity. As indicated in Tables 1 and 2, Shellbiotic improves the breaking strength of both eggshell and bone significantly, while bone ash remains constant – which indicates that the matrix to which the calcium has been linked has been improved significantly.

| Parameter | Negative control | Shellbiotic |

|---|---|---|

| Shell weight (g) | 6.10 | 6.16 |

| Shell thickness (μm) | 360.20 | 361.52 |

| Eggshell breaking strenght (N) | 40.69b | 42.69a (P<0,05) |

| Parameter | Negative control | Shellbiotic |

|---|---|---|

| Tibia weight (g) | 5,65 | 5,77 |

| Tibia ash (%) | 50,68 | 50,65 |

| Tibia breaking strength (N) | 205,42b | 221,86a |

Especially when hens grow older and their body weight becomes heavier, good bone strength is important not only for general (mating) activity to move around the poultry house, but also, more particularly, to make sure they can eat and drink in the time available and move easily to the nesting area. This latter activity prevents increased incidence of floor eggs, which often presents a greater risk of egg bangers.

A field trial with Shellbiotic in broiler breeders in a Spanish integration showed that the % of floor eggs became significantly lower in the treatment group once the hens were older than 48 weeks of age. As there was no difference before, this might indicate that the hens’ activity and moving ability remained better as they got older. The performance data over the whole trial period when Shellbiotic was added (32 weeks of age until 64 weeks of age) is presented in Table 3. The farm had a history of not reaching peak production very easily and then experiencing a rapid drop in production after peak was reached.

| From 32 to 64 weeks of age | Control Group | Shellbiotic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. HD production | 58.2 | 64.5 | <0.05 |

| Total egg production | 134.44 | 149 | <0.05 |

| Total hatching egg production | 125 | 141 | <0.05 |

| % hatching eggs | 93.0% | 94.6% | <0.05 |

| % floor eggs | 4.2% | 3.3% | <0.05 |

In addition to the significant improvements in performance, a slight improvement in mortality (0.20%) was observed as well.

Conclusion

In poultry production, the hatchery is regarded as a crossroad where all the traffic converges and where traffic lights control the traffic’s speed and flow. If the lights do not function well, accidents can happen. This is the case when hatching eggs become contaminated, which results in an increased number of egg bangers by which day-old chicks become contaminated and this is then spread over several broiler houses or farms.

Improving the activity and quality of the hen, improving bone integrity, and improving both internal and external egg quality result in lowering the risk of bacterial contamination of the egg and, hence, assure a smooth and continuous flow through the crossroad.

References are available on request.