Receive all our future audio articles in your mailbox

Dairy cow diseases can lead to production losses and mortality, resulting in decreased profitability for farmers. During their gestation and lactation cycle, high-producing dairy cows undergo several challenges that increase the risk for metabolic stress and the resulting negative effects on health and production. For a long time, the industry relied on antibiotics to solve several diseases, lower mortality, and minimize performance problems. Today, this is no longer possible.

With a growing world population, providing enough food is becoming a big challenge; especially sustainably and safely produced food. In addition, consumers increasingly want healthy food from antibiotic-free raised animals, as this will help preserve the ever-diminishing arsenal of antimicrobials effective in medicine for as long as possible. This is why, today, increasing bacterial resistance against antibiotics—tied with the increasing demand for animal protein—is challenging the agricultural sector to look for more sustainable and safe production of cattle products.

As well as reducing antibiotic use, key issues for different stakeholders worldwide is ensuring animal health and welfare. Alternative approaches that reduce the need for antibiotics and prevent/treat diseases are becoming essential. Focusing on creating a more efficient immune system can contribute to this goal. By boosting the immune system, nutritional strategies can minimize the use of antibiotics and maximize sustainable and safe food production.

Antibiotics under discussion

Antibiotics have become integral to today’s livestock production, including dairy cattle. Recently, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in animal agriculture has been subjected to critical examination by governments and consumers worldwide. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a threat to the health and well-being of humans and livestock (Laxminarayan et al., 2014). As a response, several countries are prioritizing reduced antibiotic use in livestock through various regulations and industry guidelines.

Targeted antibiotic treatment in dairy cattle

The biggest need for antibiotics in dairy is for diseases like retained placenta, mastitis, and metritis. When administered, they have a huge negative effect on milk production. When administered antibiotics, the milk from the cow is collected separately from the milk tank and will not be processed. Since 1969, the standard recommendation was to use antibiotics when drying-off cows. However, this old habit is encountering opposition. For example, in the Netherlands, the preventive use of antibiotics when drying off was banned in 2012. Today, farmers are only allowed to use antibiotics on cows that are at an increased risk of developing mastitis; so-called dry cow therapy. There, the tipping point between an acceptable increase of udder inflammation and helping reduce the use of antibiotics is considered at a somatic cell count of 150,000 cells/ml for heifers and a count of 50,000 cells/ml for multiparous cows, no more than four weeks before drying off and as found at the last milk recording.

Mastitis is the most expensive and recurrent disease in dairy farming with the inconvenience and costs associated with clinical mastitis clearly visible. However, subclinical mastitis cases (cows with elevated somatic cell count) are responsible for the greatest losses (e.g. reduced milk production and fines). Still, large quantities of preventive and curative antibiotics are used in the battle against mastitis worldwide. To reduce this antibiotic use, and therewithin antibiotic resistance, it is crucial to focus on supporting the cow’s immune system.

Two stressful periods

Many factors influence animal health and production (genetics, environmental stressors, diet, metabolic status, and the immune system) that all interact and make it difficult to determine an action plan (Figure 1). Like all animals, dairy cows have natural self-regulating mechanisms to respond to challenges (changing behavior, physiological adaptations, or activating the immune system). The mechanisms behind these responses require energy and impact production.

High-producing dairy cows undergo several challenges throughout the whole production cycle, with the main focus on the drying-off period and around calving/onset of lactation. Compared to these periods, the responses to environmental and metabolic stressors (e.g. heat stress, acidosis, mastitis) outside of the transition period tend to have lower negative effects because the cow is in a positive energy balance and experiences fewer immune pressures.

Mastitis is the primary instigator

As previously mentioned, mastitis is a global issue and the cause of a lot of antibiotic use. When focusing on the mammary gland, the prevalence of new infections is most common at drying off and after calving. Estimations are that over 60% of all new infections originate from the dry period alone. When the cows are dried off, most farmers abruptly stop milking them. This stresses the mammary tissue, making it more sensitive to infections. Since milk production is still relatively high, there is an increased risk of milk leakage and the pressure in the udder increases so that the teat entrance remains open during the first days of the dry period. This is when bacteria will infect the udder and cause (sub)clinical mastitis. Applying local antibiotics or the combination of an antibiotic with a teat sealant can help prevent infections.

Dealing with the drying-off period

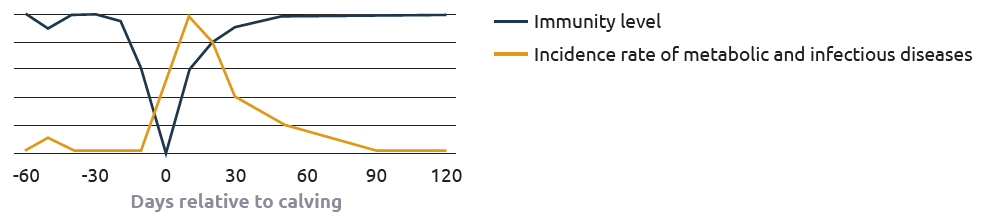

The most vulnerable period for infection is situated around calving. Complex processes take place to enable the animal to give birth and cope with the change in energy and nutrient requirements needed to produce milk. This often leads to an energy imbalance. A shortage in energy can never be prevented around calving but the level of this deficiency can be limited. Due to hormonal changes at the end of gestation, the period around calving is associated with immune suppression (Figure 2), making her more sensitive to infections. A lot of energy is then invested in lifting the immune response to optimal performance. An activated immune system can cause a glucose consumption of up to 2.16 kg per day (Stoaks et al. 2015), which corresponds with the amount of glucose used to produce 31.5 kg of milk (Reynolds, 2015). This will result in a significant drop in milk production.

Handling a hard start to lactation

A suboptimal start of lactation will influence the rest of lactation and can lead to lower feed efficiency, poor fertility, susceptibility to diseases, etc. In fact, the reason for higher culling rates often results from a suboptimal transition period. For this reason, a lot of cows are automatically directly or indirectly treated with antibiotics. The idea of this approach is that it will prevent an immune system drop around calving, saving the cow energy which she can then invest in production performance.

Increasing resilience: Boosting the immune system

It is obvious that the immune system needs to be efficient during times of stress. The interaction between the pathogen and the immune response will determine the effect of the infection. In a normal situation, with a well-functioning immune system, the cow is able to defend the body against pathogens. Since antibiotics help to lower the infection pressure, replacing them requires a strict pathogen prevention strategy. A good strategy implies good management and nutrition, as well as the inclusion of functional feed ingredients (FFIs) and additives to creating optimal circumstances to support the efficiency of the immune system— together with good liver function—and to minimize the gap between nutrient input and nutrient output (i.e. milk production).

Agrimprove strongly believes in the necessity of supporting cows in the vulnerable period of transition. They work to keep cows healthy and to support milk production. This combined transition strategy of improving immunity and supporting gut health contributes to a strong decrease in the need for antibiotics and results in more resilient cows with higher profits; making milk production more sustainable, safe, and profitable.

Conclusion

Due to growing awareness of AMR, the transition to antibiotic-free cattle products will continue. In order to succeed in this new environment, it is important to understand the needs of dairy cattle to produce efficiently, sustainably, and safely. By focusing on increasing the overall immune status of high-producing dairy cows, Agrimprove can—together with you—strive towards higher longevity with less antimicrobial use.