Written by Frederik Gadeyne, Researcher Ruminants

Imagine a cow with her calf by her side happily grazing in a spring meadow. This fairytale image is made possible by microbes. Just like all animals, ruminants rely heavily on the synergy between themselves and the microbes in and around them. This interaction between animals and their microbial guests is of utmost importance for the animals’ health and productivity. The bacteria, fungi and protozoa present in the rumen allow cows to digest dietary components that are otherwise underused, especially fiber-rich components such as grass and hay. And the impact of microbes on productivity and health is no different for calves – starting a long time before they begin to ruminate.

A calf’s microbiome under full development

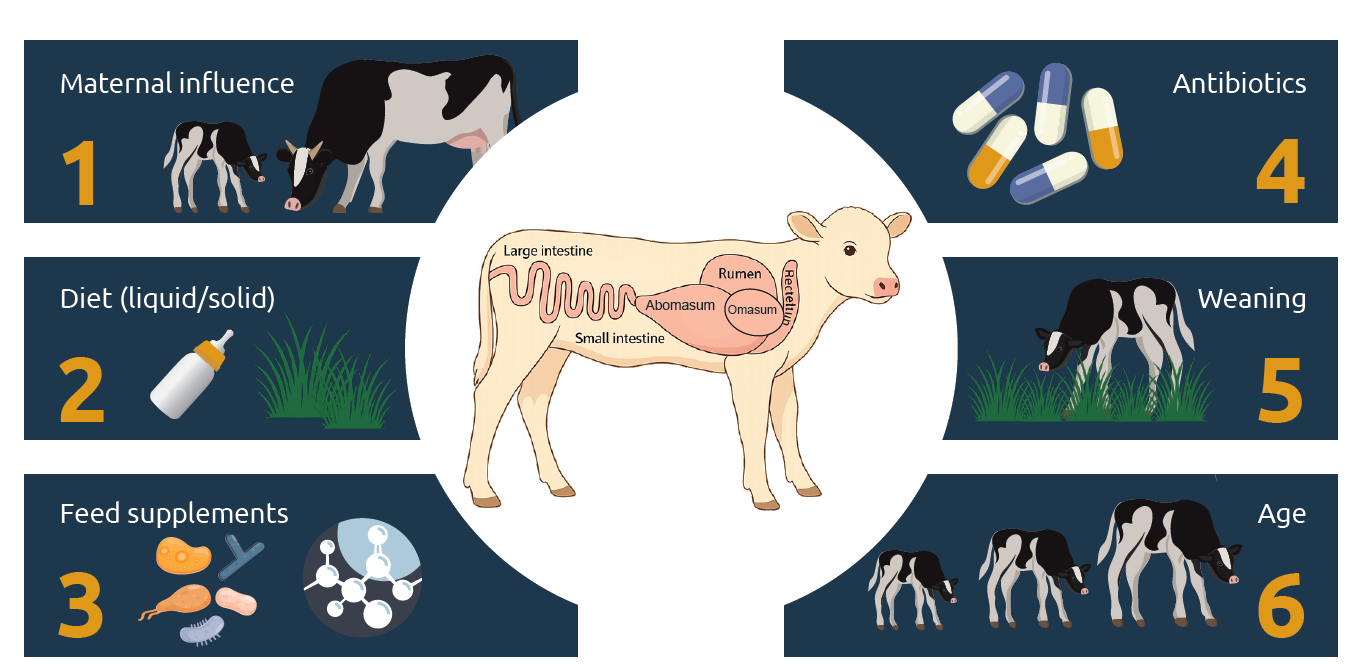

The gastro-intestinal microbiome develops quickly after birth. There are a number of ways that microbes can enter the calf’s developing rumen and lower intestinal gut. This includes the transfer of microbes from the dam’s vaginal or fecal microbiota, inoculation from the barn environment in which the calf was born, and derivation from the microbiome present in the cow’s colostrum (Figure 1). In the last decade, scientific knowledge has been expanding rapidly, along with the development of sequencing tools for analyzing microbes. Our knowledge of microbes in ruminants grows day-by-day, but one thing is already clear: the colonization of the calf’s gut is a process that takes time and depends on multiple factors such as milk and solid feed intake, dietary composition, antibiotics usage, age and environmental pressure. The gut’s microbial composition is under full development, especially during the first days of life, and this process keeps on developing until weaning.

Inhabitants of the gut change over time

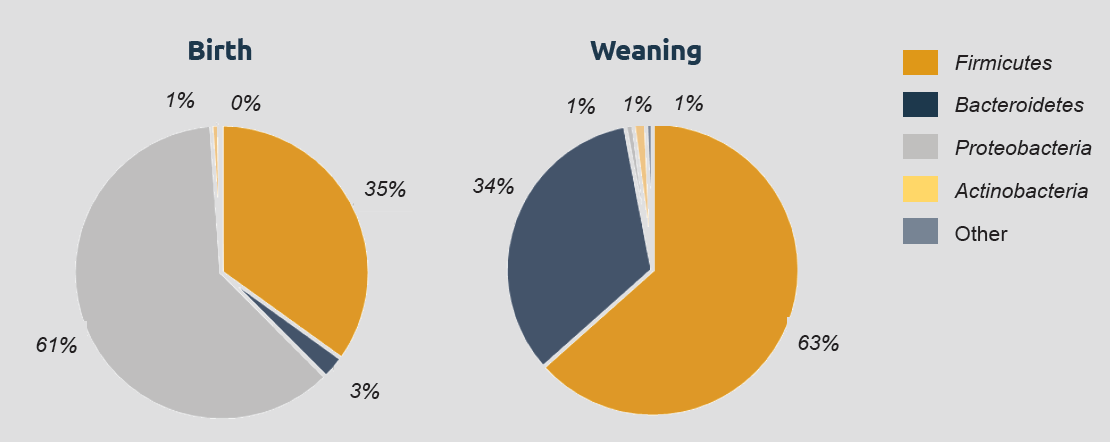

A wide variety of microbes – including fungi, viruses, protozoa, and, most of all, bacteria – reside in the gut of ruminants. The bacterial species can be classified in different families, orders, classes and phyla. The most dominant phyla present in the developing rumen and lower gut of newborn calves are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. The relative abundance of the bacteria within these phyla groups evolves constantly from birth until weaning – and this includes well-known bacterial genera such as Lactobacillus (part of the Firmicutes) and Prevotella (which belong to the Bacteroidetes) (Figure 2). Most of the bacteria in the gut are desirable, but some are harmful, like Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhimurium, the most famous members of the Proteobacteria phylum.

A more diverse microbiome creates resilience against pathogens

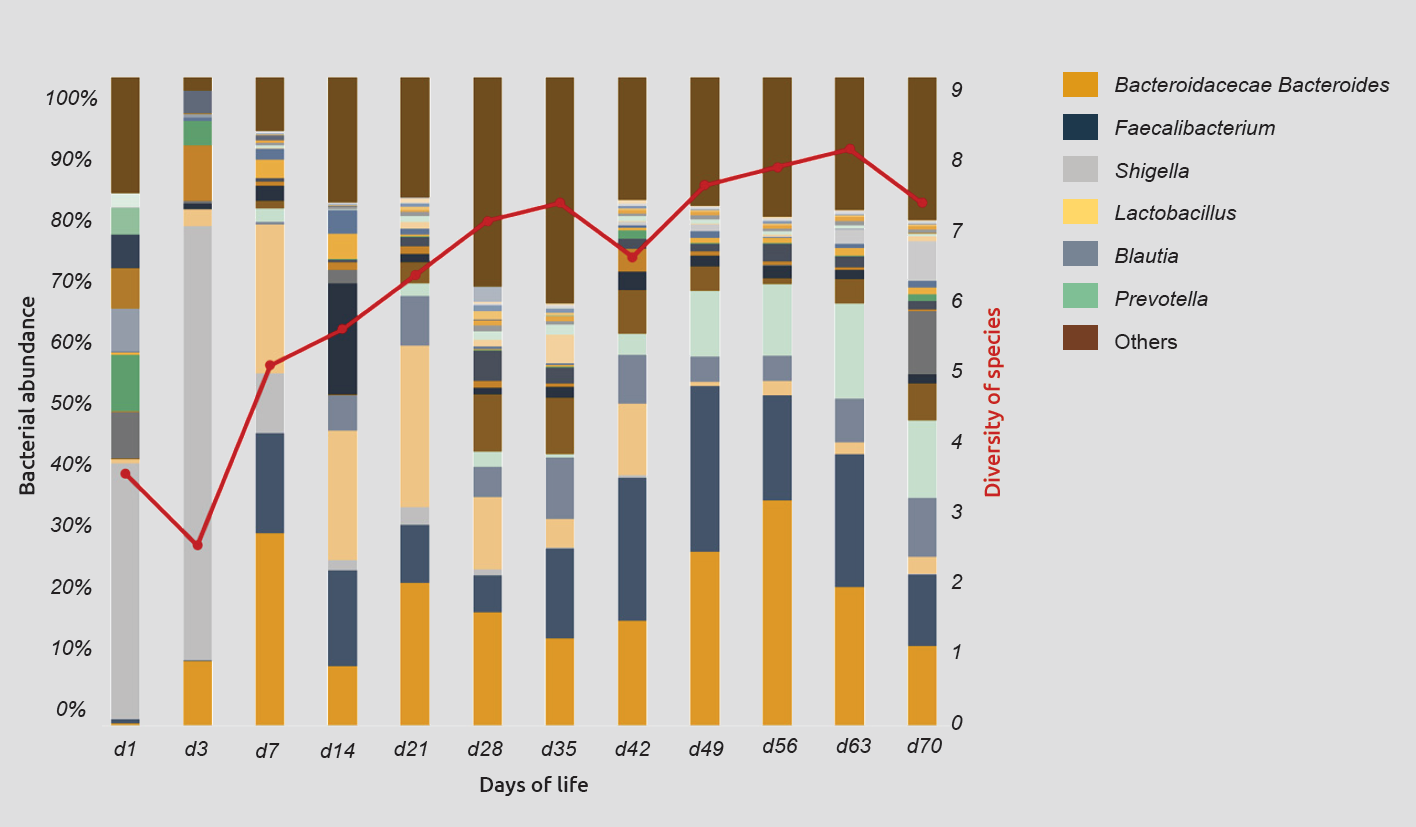

On top of that, in the earliest days of a calf’s life, the bacterial composition is not stable – it’s a process that goes on continuously until weaning. Colonizing bacteria come and go, but with age the bacterial community becomes more and more diverse, especially during the pre-weaning period (Figure 3). It is well known that a more diverse microbiome creates resilience against pathogens. The presence of many types of micro-organisms prevents pathogens from growing above harmful thresholds. A richer microbiome allows growing animals to handle more harmful situations and more pathogens, thereby lowering the risk of hampered gut health. As long as the calf’s microbiome is not fully established, calves are (much more than adult cows) prone to intestinal pathogen colonization and, hence, gastrointestinal diseases. The ratio between the two biggest phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, is widely accepted as a marker of gastrointestinal microbiota dysbiosis. Changes in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio can be linked to various diseases like neonatal calf diarrhea.

Challenges in young calves

Calf diarrhea – commonly called ‘scours’ – is still the No. 1 problem in the calf rearing business. Many pathogens can be responsible for this, including rota- or corona-virus, Cryptosporidium parvum parasites, and bacteria such as E. coli or Salmonella. The prevalence of these pathogenic bacteria is highest in the first weeks of life – not coincidentally the weeks in which the calf gut microbiome is not yet established. Neonatal calf diarrhea has a big impact on the young animals’ intestinal development – on the epithelial cell lining, as well as on the microbial composition. As a consequence, this has a negative effect on growth performance. Moreover, respiratory issues often occur when calves experience stressful situations. So, interventions to prevent scours and respiratory issues reduce the need for anti-microbial treatments – helping farmers reduce feeding and veterinary costs, and, hence, generating a more sustainable income, not to mention lowering the build-up of anti-microbial resistance by the animal sector.

Unlocking the full microbial potential

Supporting calves during those vital first weeks is necessary to have a successful rearing period. Besides good management practices, vaccinations and delivering sufficient amounts of colostrum, a farmer does not have many nutritional tools to support a quick and proper development of the calf’s microbiome. Solid feed intake is limited in the first weeks of life, when calves still rely heavily on milk intake. Hence, adapting the composition of the calf milk replacer (CMR) is the fastest, easiest and most effective way for farmers to support the calf’s microbiome development and associated health early in life. It is well recognized that the earliest days of life are key to supporting gut health in young calves. It was recently found that the second week of life is a key moment for early nutritional intervention, when the abundance of milk-digesting bacteria (such as Lactobacillus) increases and the abundance of harmful bacteria (e.g., Proteobacteria and Shigella) declines. Having a stable and fully established microbiome as soon as possible allows calves to grow in the most efficient and healthy way.

Sustainable MCFA shape gut health

Agrimprove experts work every day to develop sustainable solutions that help farmers limit calf diseases as effectively as possible. Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) are one nutritional option, but they are often not sustainably sourced as they are derived from palm kernel or coconut oil. That’s why Agrimprove researchers developed Aromabiotic® Calf, a health-supporting CMR supplement, based on sustainable MCFA that originate in waste streams. A large experiment was set up to evaluate the effect of Aromabiotic® Calf on growth, gut and lung health in dairy calves at the Blanca from the Pyrenees research farm in Spain. Sustainable MCFA positively influenced gut and lung health when given as part of the CMR, and they exerted a positive effect on maintaining intestinal homeostasis, especially when the calf’s microbiome was under full development. Two abstracts on this new scientific evidence were presented at the 76th EAAP (European Association for Animal Production) Annual Meeting in Innsbruck, Austria.

References are available upon request.